Rhythmic oscillation can be found everywhere in nature, from cosmic (video) to subatomic scales, and everything in between.

In addition, all known organisms employ biological clocks, and from the moment of conception, mammalian life is in the presence of perceptible biological rhythms such as breathing and circulation.

We are a species of drummers and dancers, moved on a primal level by rhythm and tone. Soothed by the heartbeat of another.

And yet, since rhythm – in the musical sense – is often more complex than the simple periodicity found in nature, even the most musically-gifted of us can sometimes struggle to master it.

Which brings me to the topic of this post: are you comfortable with rhythmic guitar (particularly: strumming)?

If you’re anything like me (and most beginners), I suspect the answer is ‘no’.

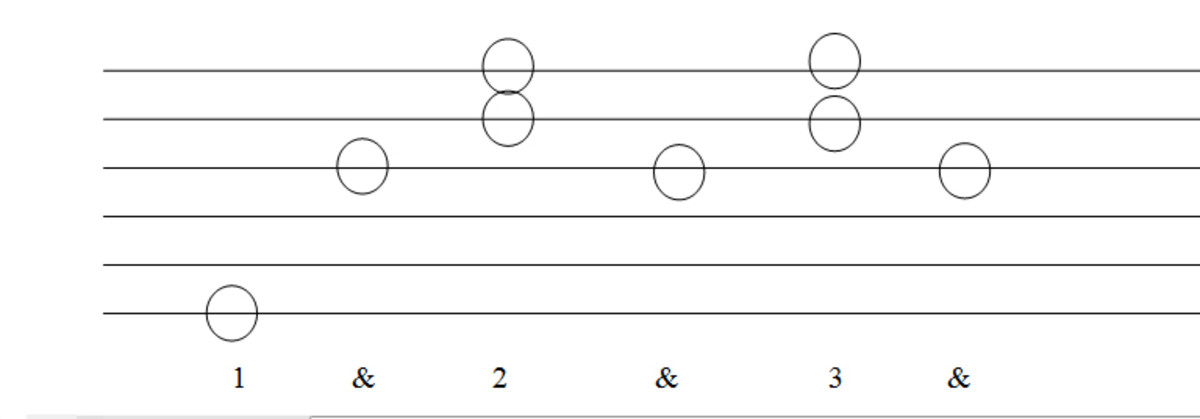

When I first started playing, in blissful ignorance, I gravitated towards a single strumming pattern, happily trying to shoehorn it into every song. I didn’t know when or why that particular pattern lodged itself in the ‘guitar’ drawer of my mental filing cabinet, but obviously it’s not advisable to use a 4/4 strum rhythm during a song with a 3/4 time signature.

That was my first strumming problem, which I initially solved by just strumming downwards on each major beat. While this solution may indeed represent the simplest guitar strumming pattern, it is also the most mind-numbing and unmusical one.

The second problem I’ve encountered has been trying to strum one rhythm while singing another, which can feel a little like trying to simultaneously rub your belly and pat your head.

I wasn’t expecting this. Having played piano for many years, I never found it difficult to do one thing with my left hand and another with my right. But I guess doing one rhythmic thing with your hands and another with your voice is a horse of an altogether different colour. More like beginner drumming: trying to co-ordinate the right rhythm, limbs, and drum types. A truly non-trivial task.

Perhaps you’ve already taken the initiative and tried to solve the time signature/strumming/singing problem on your own, and encountered down-up strum diagrams which make you so obsessed with counting out the beats and strumming in the right direction that you don’t have any mental resources left to devote to chord changes or singing.

Maybe you, like me, feel that music should be more intuitive and enjoyable than that; that we should automatically know which strumming pattern and rhythm are most appropriate for any song. I think it’s possible that the answer to this is both yes (in the sense that a comfortable strum trumps one during which you constantly worry about direction and ‘correctness’) and no (in the sense that it’s only through dedicated and mindful practice that strumming patterns start to feel natural).

In effect, practice automates the rhythmic part of guitar, freeing up explicit mental focus for technique, chord changes, and/or singing.

Rhythmic strumming ‘muscle memory’ will develop faster with isolated strumming over-training: even when you think you’ve got it, keep going (to cement the neural circuits for that action). If you combine this with increased exposure to music employing all kinds of different rhythms (to develop a better general feel for musical rhythm), it should lead you towards relatively effortless strumming, even when combined with singing.

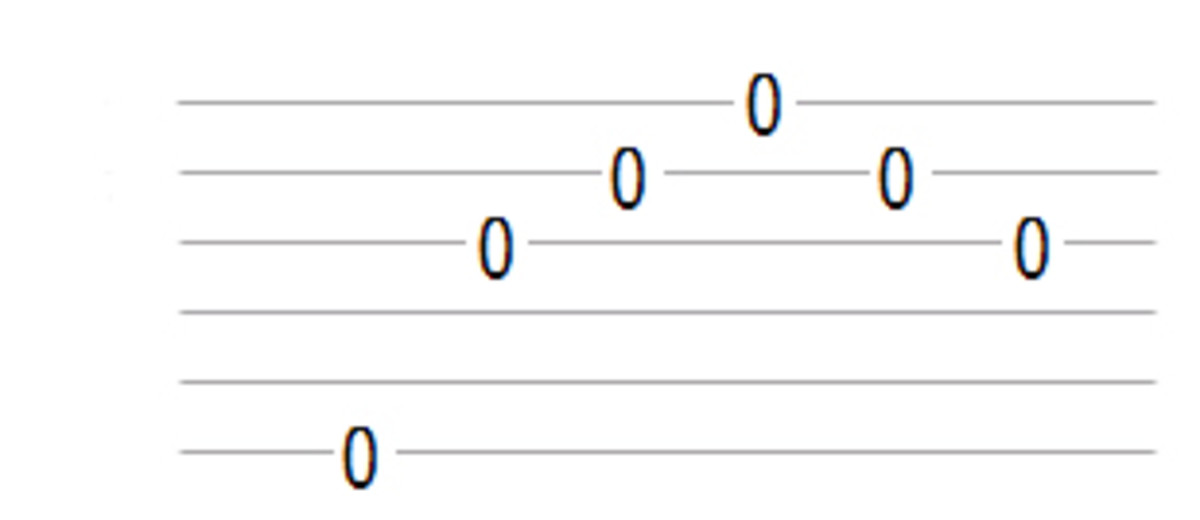

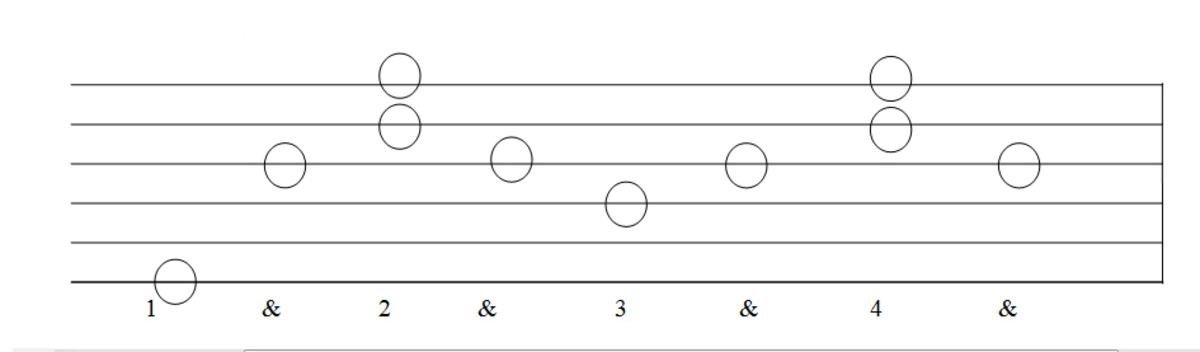

So go learn some pre-existing popular strumming patterns! Start with open strings (no chords). Don’t pause after each loop of the pattern: try to seamlessly integrate loop after loop so that your brain learns it without interruption from the start. When you feel comfortable, introduce a chord change each time the loop repeats.

What to practice, you ask? Here’s the best resource I’ve found for common 4/4 strumming patterns (incidentally, that single strumming pattern I was ‘inexplicably’ gravitating towards turned out to be the first one). For 3/4 strumming, try patterns 10-12 here. Beyond these patterns, I would recommend listening to some of your favourite songs and picking out the strumming pattern (including how it may change between the verse/bridge/chorus). Then copy those strumming patterns and try to play along.

The more you do this, the more you’ll get a feel for which strumming patterns:

(a) you like best, and

(b) fit best with different songs.

If you’re looking for a rhythmic challenge (and a cool song to play), try Ben Harper’s Another Lonely Day (but listen to the rhythm first!).

Ultimately, what you want to do with strumming is to create a consistent, fluid, and textured musical backdrop on which to unfold a song’s melody. You don’t want pauses where they don’t belong, or sudden changes in tempo/volume, because you don’t want the backdrop to feel fragmented (unless the piece is intended to sound that way). To borrow a lovely turn of phrase from guitardomination.net: “The fretting hand is the brain, but the strumming hand is the soul“.

You may think you are strumming and chord-changing smoothly, but I would highly recommend recording yourself and playing it back. You’ll be amazed at the things you hear on a recording that you don’t even notice while you’re concentrating on playing. For beginners struggling with smooth chord changes while strumming, there is apparently something called the ‘transition strum’ (although it does seem like a bit of a crutch, and not something you want to get used to!): instead of breaking the rhythm, just strum the open strings (softly) once, as you switch to the next chord. Keep in mind that this will usually sound fine between open chords (the open strings usually contain at least some of the notes in your chords), but that it usually won’t work so well between barre chords featuring no open strings.

A final round of tips that I’ve already mentioned in previous posts: fret as near the proximal fret bars as possible (to prevent buzzing), press down hard enough to properly shorten the strings (for a clear ring), and don’t accidentially mute strings adjacent to your fretting fingers (unless this is strategic, like muting the low E string during a B minor chord). You can also play around with some variations, to add some sonic spice to repeated chord progressions. For example, you could try modifying a regular chord (e.g. making it into a 7th or sus), or perhaps occasionally strumming only part of a chord (instead of the entire chord).

Many more rhythm guitar skills (beyond strumming) remain, but we’ll come to those another day.

Do you have any awesome tips for improving strumming? If so, I’d love to hear from you. Tweet at me (@acnotesblog), find me on Facebook (www.facebook.com/acnotesblog), or leave a comment below.

Happy playing!

P.S. Song of the day: Untouched by The Veronicas

If you like Untouched, please consider helping to support Acoustic Notes by checking out a The Veronicas’ album here.

RELATED POSTS