Imagine the practice scene in every dance movie you’ve ever seen.

The instructor always counts out “5-6-7-8!” before everyone launches into the dance, right? The instructor is ‘counting the dancers in’ so that everyone starts dancing at the same time, with the same timing.

Just like dancing, music behaves in a particular way in time: every song has a particular rhythm. Music is all about rhythm.

Because most people have a natural sense and understanding of rhythm, they can easily dance and sing without having to be taught the music theory underlying rhythm. It’s even relatively easy to play music you’ve heard before on an instrument, without necessarily needing to consult the theory.

But to play sheet music you’ve never heard before, to write sheet music, and to choose the correct strumming pattern for a song, you need to understand the concept of the ‘time signature’. Maybe you’ve tried strumming the chords to the songs you’ve been practicing, and have noticed that you can’t quite make the strumming pattern match up to the timing of the singing. If so, you are in good company. Also: this post is for you.

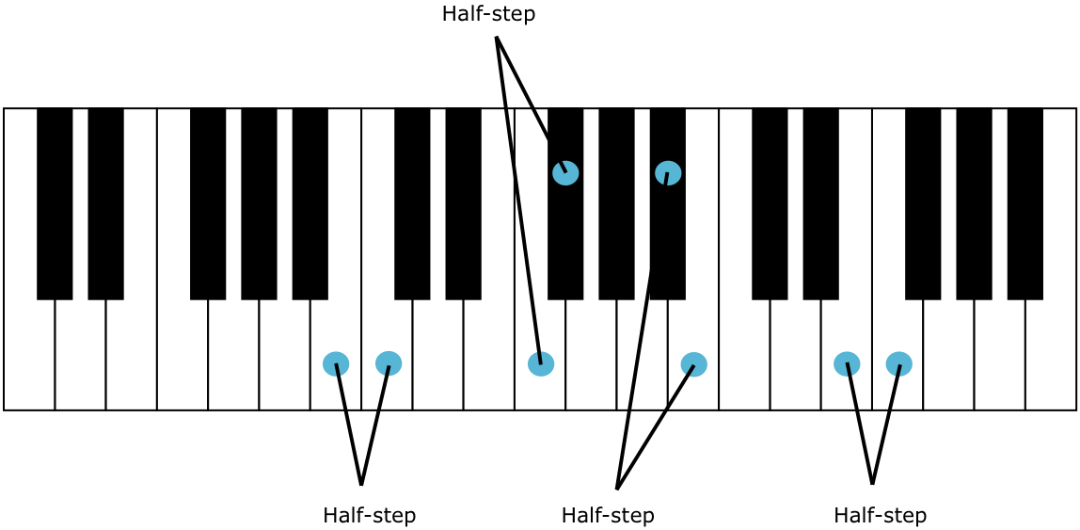

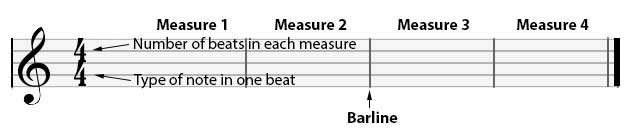

Musicians write down music – and its timing – on a staff (divided into compartments called ‘bars’ or ‘measures’). Each bar contains a certain number of beats. The number of beats per bar is called ‘meter’. Meter is indicated on sheet music using a time signature: two numbers stacked on top of each other at the beginning of a piece:

Image credit: http://strumspot.com

There a few possibilities for how (relatively) long each beat can be. Musicians use specific note symbols to represent the relative length of each note’s beat:

The actual length of each beat depends on something called ‘tempo’: how fast or slow the music is being played. If we set a metronome slow, to sixty beats per minute, each crotchet would last 1 second. In practice, the tempo of music pieces is usually faster than this.

For example, popmusictheory.com figured out that the most common tempo of 2015’s top 100 songs was 120 bpm. And, depending on how fast you like to work out (especially running), you can use a chart to find the ideal song tempo and create the perfect workout playlist (you can find the tempo of any song here).

But let’s get back to the theory. The most common time signature is 4 crotchets per bar: each bar contains 4 beats, and each beat is a quarter note long. In time signature notation, this is written as 4 over 4 (or as ‘c’ for ‘common time’). The bottom number tells you which type of note (‘4’ indicates ‘quarter’-notes a.k.a. crotchets), while the top number tells you how many of these notes per bar (before you start over again in a new bar).

Typically, the first beat of every bar is accentuated (in the same way that some words in a sentence are emphasised), so you would count out the meter as “1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4″ etc.

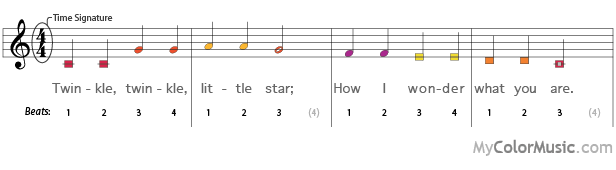

Let’s apply this to something simple, like Twinkle Twinkle Little Star:

Image credit: http://www.mycolormusic.com

As you can see, in 4/4 time every beat in a bar doesn’t have to be a quarter note (or even any note – there can just be silence during some beats), but together the beats in a bar must add up exactly to the time signature. For instance, in Twinkle Twinkle, the first and third bars contain 4 crotchets each, the second and fourth bars contain 2 crotchets and 1 minim each. Remember that 1 minim beat is equivalent in length to 2 crotchet beats, so each bar still adds up to four crotchet beats.

What emerges from exactly how the beat lengths and accents (and silences) are arranged is the overall rhythm of the music. Different rhythms can make music feel completely different, for example ‘swing’ versus the Latin rhythms (e.g. cha-cha).

Now try counting out “1-2-3-4” to something a little more complex, the Beach Boys’ Surfin’ USA:

Other common time signatures apart from 4/4:

- 3/4 indicates three crotchets per bar, also known as a ‘waltz’. Count out “1-2-3, 1-2-3” etc. Try it with Kelly Clarkson’s Breakaway:

- 2/2 (also sometimes written as ‘c’, but with a vertical line through the c to indicate ‘cut-time’) indicates two minims per bar, also known as a ‘march’. Although there are the same number of beats per bar as in 4/4 time, 2/2 time *feels* different. Count out “1-2, 1-2” etc. (like the “left-right, left-right” of a march). Try it with this piece (commonly referred to as the ‘Graduation March’; actually Edward Elgar’s ‘Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in Dmaj, Op. 39’):

There are many more possible time signatures (e.g. 6/8 or 5/4), some of which are more complex or unusual. For now it’s enough just to understand 4/4 and 3/4 in preparation for the next tutorial post: strumming patterns.

Happy playing!

P.S. Song of the day: Brown Eyed Girl by Van Morrison

If you like Brown Eyed Girl, please consider helping to support Acoustic Notes by getting it here.